How Legal Reasoning Should Age

I was listening to Winston Weinberg on Legal Innovation Spotlight at the weekend, and one part was really interesting to hear, as it overlapped with how I’ve been thinking about memory in my own work.

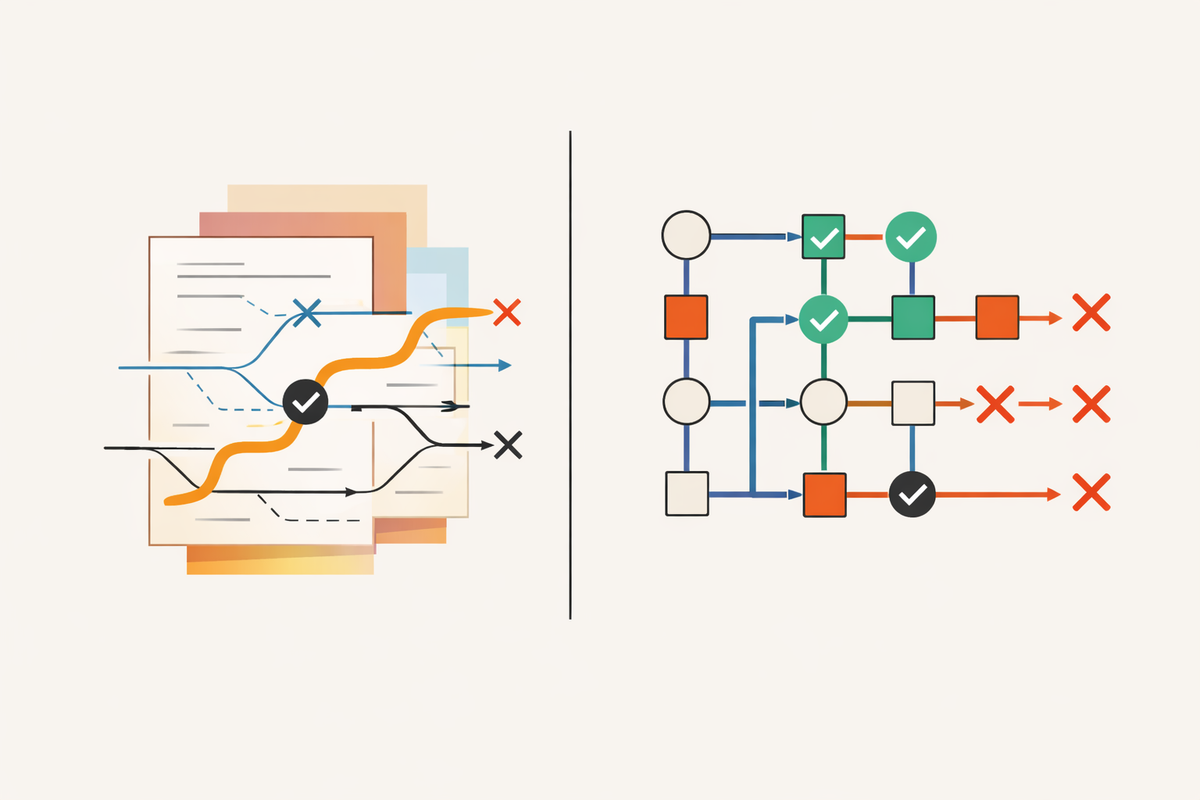

He talked about memory in legal AI not as document recall, but as capturing decision traces (not circuit traces though). Why a clause was accepted, why a fallback was chosen or why something was rejected. That distinction matters as redlines alone are a thin dataset, the reasoning behind them is where judgement actually lives.

That framing at a big vendor feels like a real step forward, though it also raises a harder design question:

If we get good at capturing legal judgement, how do we stop it being reused when it no longer applies?

Judgement is contextual, not portable

Legal reasoning is not a reusable asset in the same way a clause library is.

It depends on the client’s risk appetite at that moment, the commercial dynamics of the deal, regulatory posture, negotiation leverage, and the personalities on the other side.

Lawyers manage this today through conversation, supervision, and instinctive filtering. They know when an argument is illustrative, provisional, or simply no longer valid.

AI systems do not have that instinct, at all.

If judgement is captured without context, expiry, or intent, it, over time, hardens into precedent. What was once situational becomes default and nuance becomes pattern.

That is not a tooling problem, as ever it's a design and governance problem.

Memory needs intent, not just storage

One missing layer in most discussions of AI memory is intent.

Not every decision is meant to travel. Some reasoning is specific to a matter. Some reflects a temporary view. Some is deliberately experimental.

A practical design response is to capture judgement with explicit intent:

- illustrative

- matter specific

- preferred approach

- provisional view

- deprecated

This mirrors how lawyers already think. The difference is making that intent visible and machine readable.

Memory without intent turns nuance into accidental precedent.

Judgement should age honestly

Retention policies usually apply to documents, which is a blunt instrument.

Judgement ages differently, sometimes like a fine wine but often more like a bottle of half drunk baby milk left perched on a radiator overnight...

Arguments go stale, regulatory interpretations shift and firm strategy changes. What was defensible two years ago may be inappropriate today.

Designing for decay rather than permanence feels closer to legal reality.

That might mean surfacing the age of reasoning clearly, requiring confirmation before reuse, or reducing confidence over time rather than deleting outright.

This is not about forgetting aggressively. It is about being honest about ageing judgement.

Advisory memory, not delegated authority

There is a subtle but important distinction between informing and executing.

A system that says "previously you accepted this clause because of X" is supporting judgement. A system that just applies that reasoning is delegating it.

In regulated, high risk work, that line matters as memory should inform suggestions, not bypass review. That is not a limitation, as it's how professional responsibility is preserved through design.

Memory must be contestable

Legal reasoning evolves through challenge.

Partners disagree. Teams revisit old positions. Approaches are abandoned for good reasons. None of that is visible if memory only accumulates.

A more realistic model treats memory as something lawyers can annotate, disagree with, or supersede - not deleting it, but marking as no longer applicable.

That creates a living institutional dialogue rather than a frozen knowledge base.

Failure is not something to forget, it is something to learn from

In engineering, failed approaches are rarely deleted, in fact they often live in Git. They are documented, labelled and used to avoid repeating the same mistake.

Legal reasoning should work the same way.

- A negotiation strategy that failed.

- An argument that was rejected.

- A clause position that created downstream risk.

These should not disappear from memory. They should persist as negative examples, clearly marked as such.

The distinction matters. Forgetting hides failure. Learning from it requires visibility, context, and clear signalling that "this did not work, and here is why".

Designing for this means separating:

- reasoning that should not be reused

- from reasoning that should not be forgotten

Which is a much more nuanced challenge than simple retention or deletion

Decision traces are the frontier, though documents alone will not get us there.

However once judgement becomes part of the system, the design challenge changes. Memory stops being about context windows and starts being about control.

- What persists.

- What expires.

- What can be challenged.

- What must never be put into a process.

Legal AI maturity will not be defined by how much it remembers, but by how carefully it decides what should endure.