Beyond Summaries: Treating Law as a System of Constraints

Legal AI has spent the last couple of years getting very good at text. Summarising it, rewriting it, searching it, drafting more and more of it. All the words, all the time.

That was a necessary phase, but it's also becoming a ceiling.

Law is not just language. It’s a system of conditions, thresholds, exceptions, and dependencies. Most legal risk doesn’t come from missing words. It comes from contradictions, misapplied rules, and obligations that quietly activate under the wrong circumstances.

If legal AI is going to mature, it needs to move beyond text generation and start dealing with structure.

Quickly: what neuro-symbolic actually means

Before going further, it’s worth clearing up a term that sounds more complex than it is.

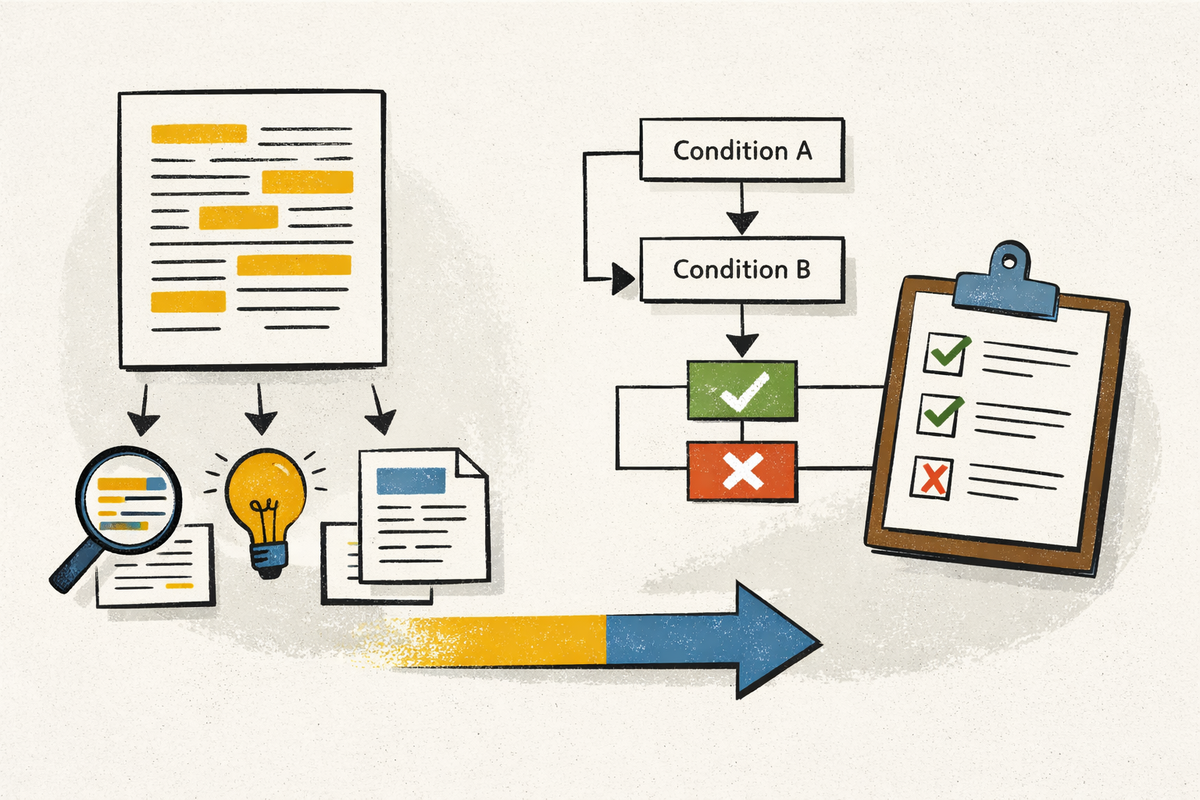

A neuro-symbolic system splits the work in two. The neural part handles language: reading messy text, extracting facts, dealing with ambiguity. The symbolic part handles rules: applying explicit conditions, checking consistency, and deciding whether something is allowed or not.

The important bit is this: language models interpret, but they do not decide. Decisions are made by clear, inspectable rules, and so i’ll refer to this approach as NS from here on.

Lawyers already think this way, even if tools don’t

You don’t need to be a lawyer to recognise this pattern:

- This clause only applies if X happens

- These two obligations can’t both be true

- This right expires after Y

- This structure is allowed only if A, B, and C are met

Legal reasoning is full of constraints and humans navigate them instinctively, then most AI tools flatten them into prose.

Summarisation hides conflict as fluent text smooths over edge cases. That’s fine for background reading, but can be dangerous for decision-making.

Why better summaries don’t fix the real problem

There’s a comforting belief that if summaries were just more accurate, more complete, or longer, the problem would go away.

It doesn’t.

A summary can be perfectly faithful to the source and still be legally wrong. It can omit the one condition that actually matters. It can resolve ambiguity that should remain visible. It can privilege one interpretation without ever saying it has done so.

A violated constraint cannot hide in the same way.

This is why recent research has started to shift, quietly, away from “is this a good summary” and towards “can this output be defended”.

Not defended philosophically. Defended operationally.

What recent research is actually pointing towards

Some recent AI work, not always tagged as legal, is exploring exactly this separation.

Language models are used to translate text into structured facts. Explicit rules are encoded separately. A symbolic layer checks whether those rules are satisfied and, crucially, can explain why they are not.

Recent work including early prototypes on regulatory compliance tasks, has shown that combining language models with explicit constraint checking can identify rule violations and suggest minimal fixes on real data.

The research isn’t claiming to replace legal judgement. It’s doing something more useful. It’s making legal structure computable.

What NS looks like in practice

This doesn’t require deep legal doctrine or giant models. You can demonstrate the idea with a very simple example.

Let's say we have an internal playbook rule:

Any contract over £100,000 must include a termination clause and must not have a notice period longer than 90 days.

Now take a short contract excerpt:

The contract value is £150,000. Either party may terminate the agreement with 120 days’ notice.

Step one

This is about interpretation. This is where the language model helps, and nothing more.

You extract facts:

{

"contract_value": 150000,

"has_termination_clause": true,

"notice_period_days": 120

}

Step two

This is about is constraint checking, again no AI required.

Rules:

- If value > 100,000, a termination clause is required

- Notice period must be 90 days or less

Evaluation:

violations = []

if contract_value > 100000 and not has_termination_clause:

violations.append("Missing termination clause")

if notice_period_days > 90:

violations.append("Notice period exceeds policy limit")

Output:

{

"status": "non_compliant",

"violations": [

"Notice period exceeds policy limit"

]

}

Only at the end do you bring language back in, to explain the result in human terms:

The contract breaches internal policy because the notice period is 120 days, exceeding the 90-day maximum for contracts over £100,000.

The key point is subtle but important. The model never decides what is allowed, its only purpose is to help translate text into structure.

Why this changes the trust conversation

This approach does a few things current tools struggle with.

- It makes assumptions explicit.

- It surfaces conflicts rather than hiding them.

- It creates outputs that can be challenged, reviewed and audited.

Most importantly, it separates interpretation from judgement. That’s how legal work already functions in practice, but it’s not how most AI systems are built.

NS systems are harder to build than summarisation pipelines, but... they are also much easier to defend.

What this enables for legal AI

Once you treat law as a constraint system rather than a text problem, different applications start to appear:

- Contract checks that flag logical inconsistencies, not just risky wording

- Policy compliance engines that explain exactly which condition failed

- Internal rule enforcement that behaves predictably

- Pre-review systems that surface issues before human review

None of this requires pretending AI is a lawyer instead it requires respecting what legal reasoning actually involves.

The gap between law as code and legal reality

It’s worth addressing the obvious adjacent idea here: law as code.

In theory, a world where legal rules are fully executable is appealing, as an engineer I'd love it. Smart contracts enforce themselves, obligations trigger automatically and then ambiguity disappears into determinism.

In practice, that world depends on something far more radical than better tooling. It depends on ambiguity being removed from law itself... which would require language, context, discretion, and interpretation to disappear overnight from how rules are written, applied and contested.

That isn’t a tooling problem, it’s a societal one.

Treating law as a system of constraints is different. It doesn’t require rewriting statutes or contracts into perfect code. It accepts that law remains human language, but recognises that many legal decisions still reduce to explicit conditions that can be checked.

NS approaches sit deliberately in that middle ground. They don’t promise self-executing law. They offer something more realistic: systems that can evaluate consistency, surface violations, and explain outcomes, while leaving judgement and discretion where they belong.

If law as code is the destination, constraint-based legal AI is the on-ramp. Skipping that step is how you end up with brittle systems that work in demos and fail in practice.

This isn’t about abandoning language models, it’s just about putting them in the right place because legal AI doesn’t need to sound smarter, it needs to behave more responsibly.

The most interesting future isn’t better drafting or longer summaries. It’s systems that can say, clearly and defensibly, "this fails because this condition wasn’t met".

That’s not a moonshot, as the research is already there. The question is whether legal tech is willing to stop obsessing over text and start dealing with structure.

For anyone who want to explore this more deeply, here's what I've been reading:

- Neuro-symbolic compliance systems that translate legal text into formal constraints and verify them using symbolic reasoning

https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.06181

- Structured neural-symbolic reasoning approaches that separate language interpretation from rule application